Michelle Bu - Payments Products Tech Lead at Stripe

This story was recorded in April, 2020. Learn more about Michelle on her blog, Twitter, and Linkedin.

Tell us a little about your current role at Stripe: what’s your title and generally what sort of work do you and your team do?

I’m the Payments Products Tech Lead at Stripe, working directly with our Chief Product Officer. I support critical initiatives and work on mitigating urgent problems across the organization. I typically spend 80% of my time on one or two large cross-organizational design projects. I spend the remaining 20% reviewing and supporting technical and product design (in particular, API design) across the organization.

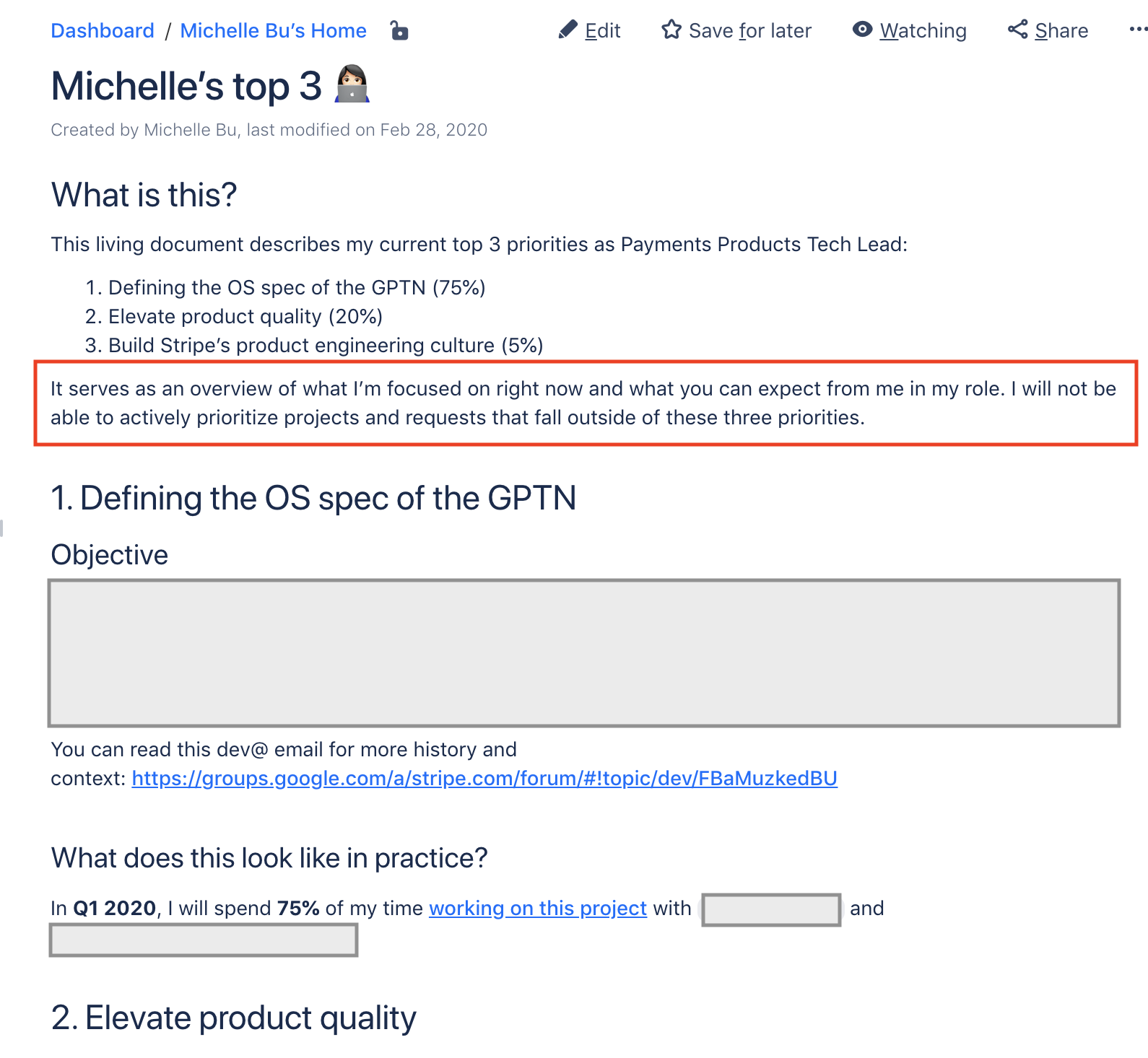

Sample of a “top 3” document I keep evergreen:

I manage two engineers who embed into high priority areas. This both helps me scale my impact and also gives these engineers the chance to dip into many areas of Stripe. Right now, one is working on the core payments APIs and the other is focused on improving integration experience. I’m still evaluated on the IC ladder—the plan is to never have more than a few reports at a time.

Michelle's podcast appearances

What does a “normal” Staff-plus engineer do at your company? Does your role look that way or does it differ?

Most engineers in Staff-plus roles at Stripe work on specific teams. There are some Staff-plus Engineers who also have a Tech Lead title, and take on broader projects across a particular product area or technical domain.

There are two kinds of Staff-plus Engineers at Stripe: those whose scope is deep and those whose scope is broad.

Broad-scoped engineers create impact by working on vague, cross-organizational projects. They tend to accumulate a lot of context across many different domains and play a support role in many projects across the org. This shape of Staff-plus Engineer is most common on our product engineering teams.

Deep-scoped engineers tend to be subject-matter experts in a specific domain. They lead ambitious multi-year projects. This shape of Staff-plus Engineer can generally be found on our product infrastructure and systems teams.

Where do you feel most impactful as a Staff-plus engineer?

This has changed over time for me as I’ve moved into my current Payment Products Tech Lead role. (For some context, Payments Products is made up of over 20 teams. We’re responsible for most of our user-facing APIs and UI libraries.)

I’ve taken to using the word “energized” over “impactful.” “Impactful” feels company-centric, and while that’s important, “energized” is more inwards-looking. Finding energizing work is what has kept me at Stripe for so long, pursuing impactful work.

When I worked directly on a team, I felt most energized when I was able to directly interact with users, whether it was helping users on the #stripe IRC channel or designing and shipping an API that users can integrate seamlessly.

In my current role, I feel energized when someone I’ve sponsored sends an announcement that they’ve shipped their work, or when I see that I’ve helped shape or shift an engineering team’s model of an important topic. It’s these teams, not me, who are doing the hard work day-to-day of building and supporting their technology. I measure my impact based on their progress and more importantly, the directionality of that progress and the alignment of their work to the company’s goals.

One concrete example from recent memory is when another staff-plus engineer and I categorized the shapes of APIs we commonly see: labeling some as flows, some as engines, some as configs, etc. The intent of this work was to build up a shared mental model and vocabulary for categorizing existing APIs and for discussing and designing new ones. Folks started to organically use these categories after seeing them once! It’s in these moments that I feel like I’m creating leverage and scaling my own impact by disseminating useful mental models and ideas.

I spend time on several of our review forums like API Review, but often these sorts of forums work more like code review. They happen so late in the design process that they tend to do a better job of preventing bad outcomes than of partnering with teams to steer great outcomes. I feel more impactful when I’m able to give engineers on product teams the tools to design great APIs.

Can you think of anything you’ve done as a Staff-plus engineer that you weren’t able to do or wouldn’t have done before reaching that title?

I’ve been at Stripe for a long time (since 2013!). While I’ve always had some amount of clout because of my tenure, my role of Payment Products Tech Lead (and the fact that I report directly to the CPO) has definitely changed how people interact with me. I’m definitely feeling lonelier at work now (and am actively working on adapting to this new normal).

One thing that’s taken some getting used to is that now folks expect me to have an opinion about whatever we’re discussing! That didn’t happen as often when I was a staff-level engineer working directly on a team. I remember being in a meeting shortly after my role change where I was a bit quieter than usual because I was a little tired. I later heard that the presenters were worried that I hadn’t liked their proposal because I didn’t say anything. This was the first time that I realized people looked to me to have an opinion and to support their ideas! I’ve been careful since then to always stay engaged during meetings and to give feedback, even if it is just to explicitly say that I haven’t fully formed any opinions yet.

It’s a bit disorienting that some folks take my opinions more seriously and are nicer to me than when I wasn’t in such a visible role. Previously, there were cases where people weren’t collaborative or would dismiss my opinions. I think it was a good thing to have experienced that. I was confident enough (and trusted enough by the organization) to give them strong feedback on their collaboration so that I could ensure things like this weren’t happening to others like me. I now worry that I’m losing visibility into where these interactions are happening.

How do you maintain empathy for other engineers’ development experiences as you spend less time programming?

I’ve only had one year in my new role, so I don’t feel too disconnected yet. Maybe this is something that will change over time. I was previously tech lead for a smaller area. In that role, I wrote a small amount of software and contributed to some of my teams’ “run rotations,” where we triaged incoming requests and fixed urgent bugs.

To maintain context in my new role, I spend a good amount of time in one-on-ones with engineers and PMs working directly on execution. This week alone, I had 12 30-minute 1-1s. I also follow every incident that’s reported at Stripe. (We have a Slack group you can join to be automatically invited to Slack rooms for each incident!) The hum of incidents is particularly useful to tune into. By reading through the details of each incident, I’m able to estimate the distance between the reality of our systems and the idealized architecture / product that I spend my days thinking about. I want to know the shapes of issues that engineers are running into, the pits of failure they’re falling into, and how the developer environment was or wasn’t supporting them in getting out of those pits. I see myself as an advocate of engineers to leadership, so it’s important for me to deeply understand our present reality.

Do you spend time advocating for technology, process or architectural change?

At this point I spend less time advocating for specific technologies or programs and more time empowering others to advocate for the technologies and programs that they think are important. I also try to be a source of knowledge and support that people can reach out to for feedback, especially on cross-cutting product decisions and on presentation of ideas to the rest of the organization.

I do work on projects where I’m explicitly thinking about idealized architecture and interfaces. However, at the end of the day, migration to any idealized state is going to be done by individual teams, so they need to feel a sense of ownership and empowerment. I spend a lot of time having direct conversations with the engineers and PMs who are actually making day-to-day decisions. The ideal outcome is that we’re able to get directionally aligned, and they’re then able to advocate for our north star within their teams and make good local decisions.

It’s a lot harder to do this for the project I’m working on right now because it involves defining the idealized architecture and interfaces for many, many teams—essentially every team working in payments! I haven’t yet figured out a scalable way to bring everyone along. Even writing documents (the most scalable way of distributing information!) is hard because different teams are (by definition) coming at the interface from a different angle and so very different framings of the problem and solution will resonate with each team. Our current approach is treating reviews of our documents like user testing: watching as individuals on teams read the documents, seeing where their cursor goes, what they’re reacting to, etc. That’s worked pretty well so far!

Designing the Payment Intents API, a rethinking of our beloved Charges API for the changing payments space, was a similarly cross-cutting project that I worked on previously. It took two years for the vision to fully land with everyone in the company. Even with that organizational buy-in, we still haven’t realized the full potential of its original idealized design. This is not a bug, though! We focused on delivering incremental value to users while proving out the design. I expect any sufficiently-ambitious design project to continue even when I am no longer on the team. An important part of making this work was writing everything down.

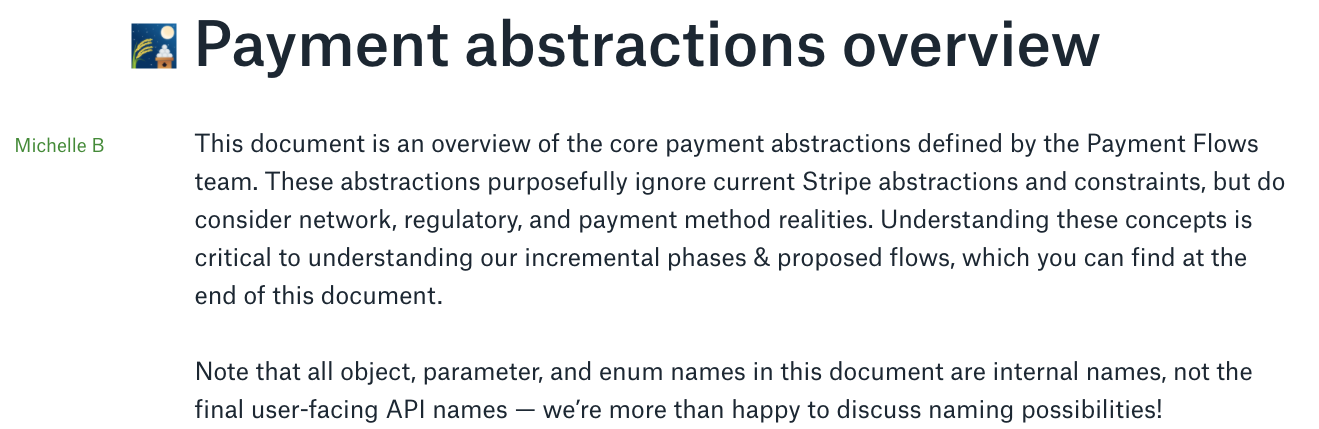

We created a canonical document that defines our idealized abstractions. Even today, folks working on that team use these abstractions as a north star:

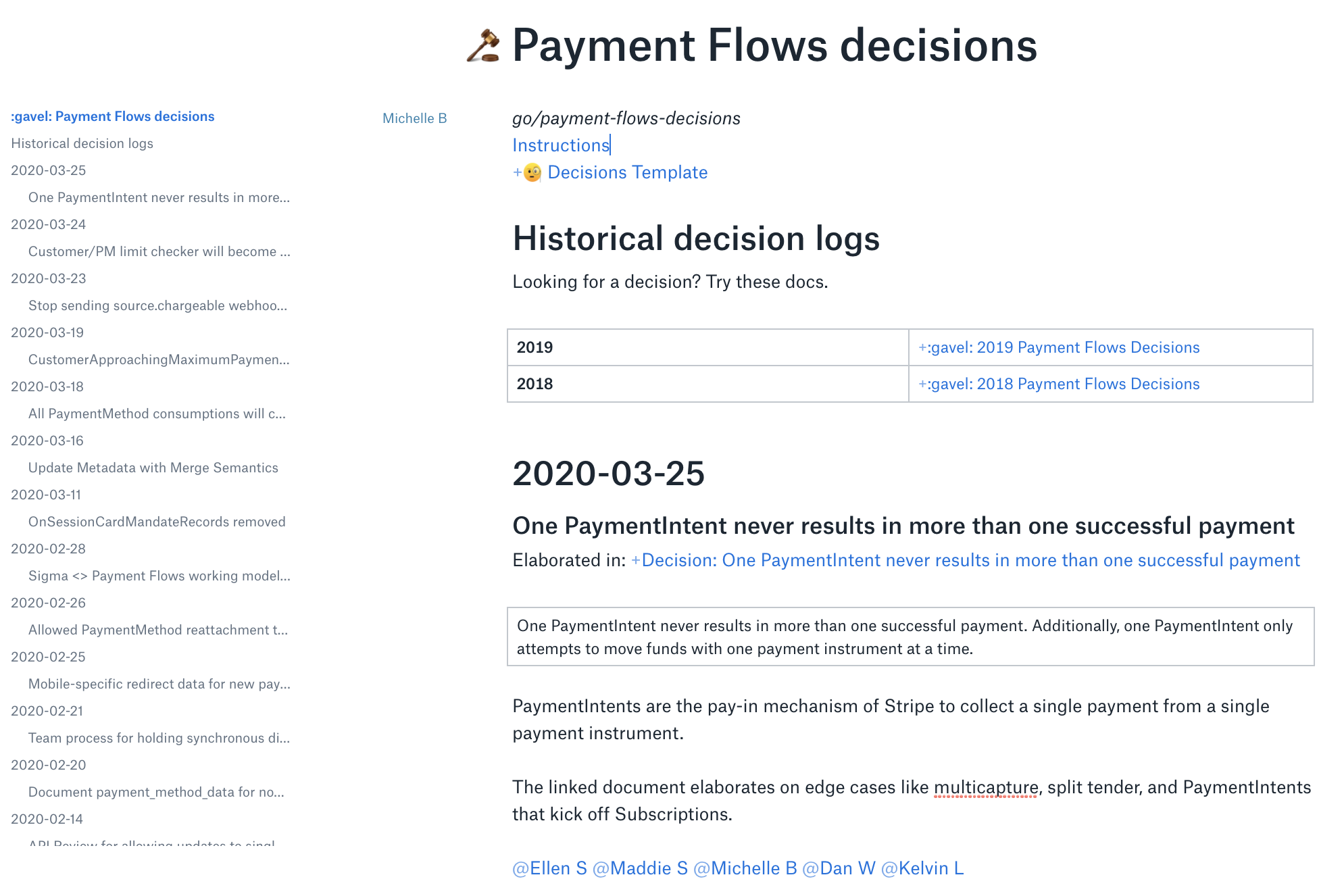

If two people asked the same question, we immediately added it to a FAQ that we kept. We took everyone’s feedback and questions very seriously and put the burden of proof on ourselves. Finally, we worked to be fully transparent in our work, even creating a decision log that anyone at the company could use to follow our progress. Each entry in the decision log concisely describes a product or technical decision, documents who was involved in the decision, and links to detailed supporting technical design documents that generally contain the full problem statement and evaluation of alternatives.

In general, I’ve found that for ambitious design projects, being extremely transparent but also explicit about whether or not you’re ready for feedback has landed well with folks who care about the topic. Here’s some wording you can find at the top of the (public) notes docs for some projects I’ve led:

Is sponsoring other engineers an important aspect of your role?

Yes, and it’s one of my favorite parts of the role! I care a lot about the people I work with—they’re the main reason I feel energized to go to work.

A big part of sponsorship for me is creating the space for ICs to do the impactful work that they care about. I’m lucky that in my current role I don’t have to spend time actively proving that I’m competent, so I can spend a good chunk of time in support roles for projects and elevating others. I rarely feel like I have to “claim credit” for work or have my name explicitly mentioned on a byline for a project I helped with (though it’s always a nice feeling when it happens). For more open-ended projects, it’s sometimes useful for me to lend my name to the project. For example, I recently kicked off a product quality mentorship program where I play more of a facilitator role, selecting mentees, pairing them with mentors, and occasionally reviewing their work. I’m not doing nearly as much as the mentors in the program are, but we were able to get this org-wide program off the ground because I sponsored it.

Day to day, I find that I can be helpful as a “rubber duck” for folks who want advice on how to navigate a complex project or resolve a technical disagreement. I find this work—helping others make progress without getting directly involved—particularly rewarding.

Finally, I always keep in mind a list of folks who are amazing at what they do and advocate for them as visible opportunities that align with their interests become available. There’s a balance here, though. I’ve learned that it’s sometimes difficult for folks to say no to me. Recently, I asked an engineer on a team I work with to send an email about some good work she had done. She told me after she sent the email that she originally didn’t want to do it, but she also didn’t want to say no to me. She then showed me the relevant entry in her “no log”:

Stripe is the first company you’ve worked full time at, and you’re still at Stripe. What was your path to the Staff level?

I joined Stripe right out of college. I actually had a slower growth curve when I joined than the other engineers in my cohort. My trajectory over my first four years was slow compared to other ambitious new college graduates. I think this was partially because I hadn’t been coding for that long (I took my first programming class in 2011 and joined Stripe in 2013), and partially because my first large project at Stripe was a 1.5-year rewrite project that was ultimately canceled.

When Stripe first introduced levels, I had been at the company for two and a half years and was leveled as an L2, a level that we expect a recent college graduate to reach in 6-18 months. I was honestly pretty disappointed, since my peers were already reaching “senior engineer” levels. At that point I’d already done a lot of impactful work, spun up most of the new product engineers who joined, and consistently jumped in to help during incidents. I worked so hard and on so many impactful things, even outside of my main projects! What else would they want me to do? Should I not help others out?

In retrospect, L2 was 100% fair based on the ladder. I worked hard and stayed late because I was naturally a bit slower than others in writing good code due to my lack of experience. I didn’t yet have a good foundation for software development, mostly because I just didn’t have enough practice yet! The impactful work I did was valuable, but also not something that I uniquely could have done. I was, at the time, solidly a high-performing L2.

In those early days, I spent a lot more time learning about the product and about the payments domain than I did writing code. I spent a lot of time helping our users (developers) with their integrations on IRC. I did smaller tasks (bug fixes, small features, bandages to paper cuts) that weren’t technically challenging but were important to those users. This sort of work doesn’t always map to growing as an engineer (though I did fine-tune my debugging skills—I’m a pretty great debugger now). I also built up relationships with other teams and other engineers by being overly helpful on Slack and on tickets and by helping teams navigate to the best solutions for our users. I helped spin up most of the new product engineers that joined in my first two years. Over time, I started having a reputation for caring deeply about our users and for being a fountain of knowledge about the product. (“Users first” is still my favorite Stripe operating principle.)

Later on I realized that during that time, while I wasn’t efficiently mapping towards growing on the technical side of being a software engineer, I was actually learning critical skills that allowed me to move very quickly from senior to Staff, and from Staff to my current role (together, this only took 3 years!). In fact, I’m pretty sure it’s the relationships I built during those first few years that made a canceled 1.5-year technical project not feel like too much of a setback to my career.

I slowly and deliberately built out my technical foundation when I worked on the first versions of Stripe Radar and Stripe Elements. I strongly believe that as long as I’m being thoughtful about my technical gaps, about filling in those gaps for the projects I’m working on, and about challenging myself with projects that take me outside of my technical comfort zone, I can build up and practice my technical skills organically. The softer skills, the connections across the company, the user focus, understanding the product deeply—these are the skills that took much longer to learn and ultimately helped me accelerate my path to Staff after I built my technical foundation.

Did you have a Staff Project?

I’ve worked very broadly on just about every component of Stripe’s product. Over time, the projects that I’ve worked on have generally spun off into their own dedicated teams, and two in particular that I worked on while I was a senior engineer might qualify as Staff projects: Stripe Radar and Stripe Elements.

With Radar, we built a brand new product from scratch, making thoughtful tradeoffs about what to build and what we could safely descope in order to get something out to users as soon as possible. When we launched in October 2016, it was one of the smoothest product launches we’d ever had. It’s since become a very successful product.

With Stripe Elements, I built out the infrastructure, designed the initial Card Elements API from scratch, and shipped to production in under 3 months. This was only possible because we did extensive dogfooding. While building Elements, I created three tiny e-commerce stores with different design frameworks and designs (of varying quality) to test the limits of its customization APIs. Since then, dozens of engineers have successfully developed in the codebase, it’s the home of the new Stripe Checkout, and most importantly, we’ve had very few regrets about its original API design. Breaking API changes are always to be expected as an API product expands and we learn more about how developers use them in practice. We did a good job validating our initial API design to avoid these breaking changes while still shipping rapidly.

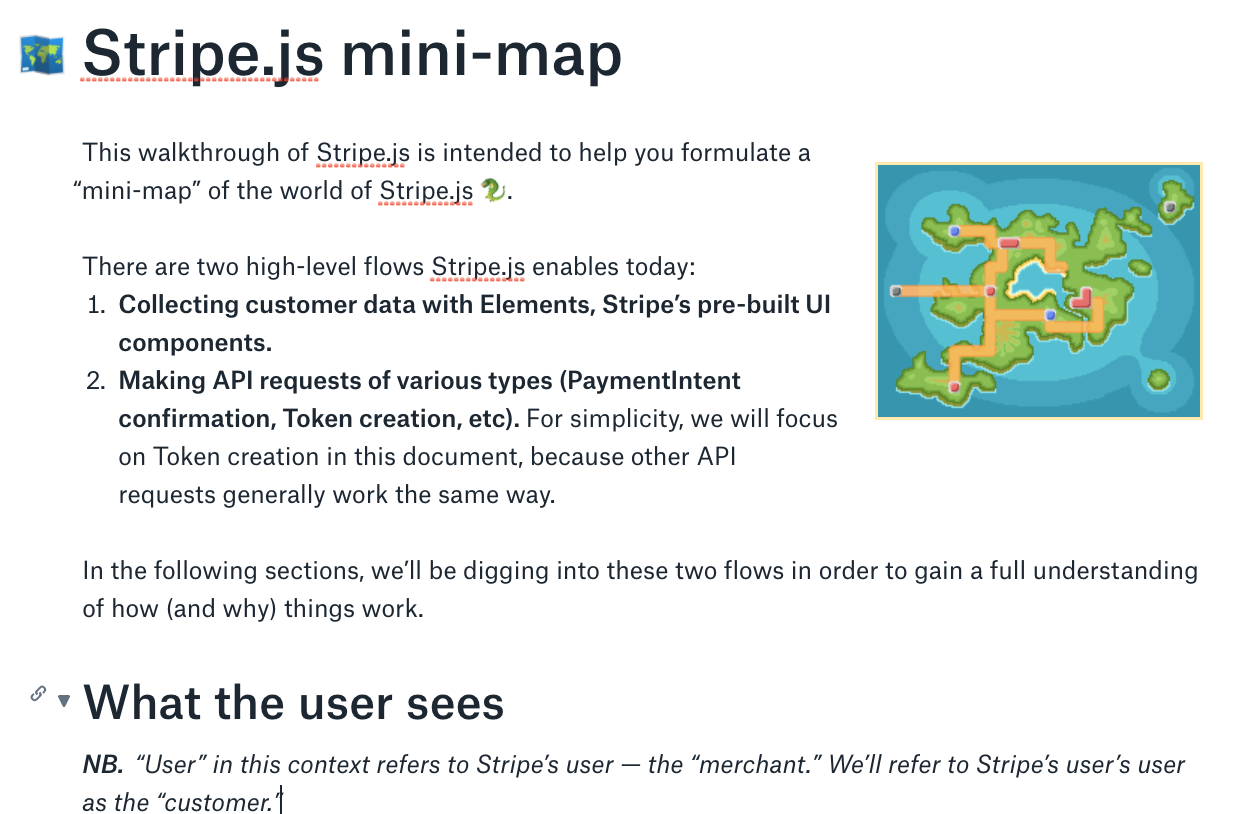

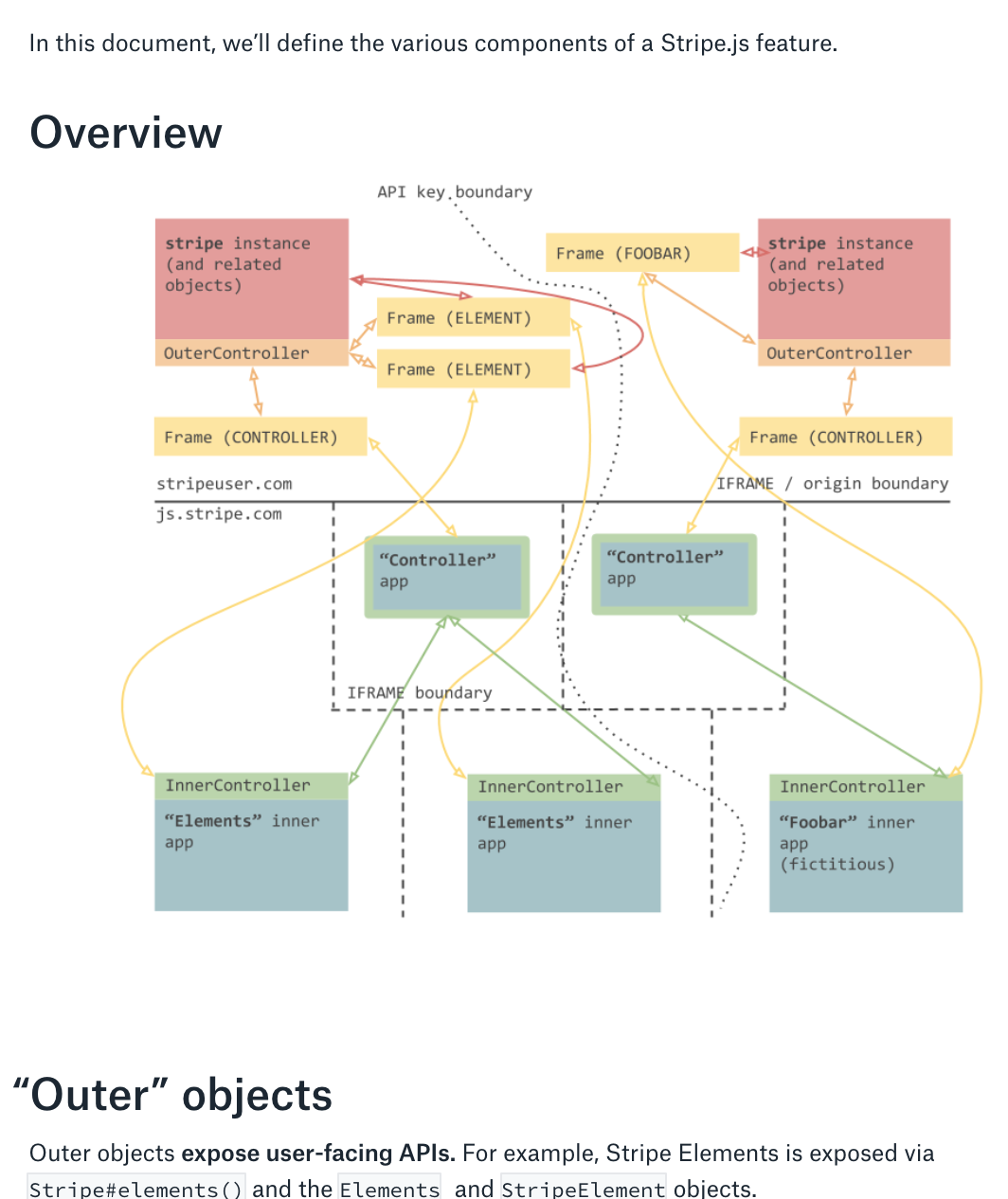

In making sure new engineers could onboard onto a pretty complex product that involved a ton of IFRAME-shenanigans, I wrote a lot of documentation. I found that telling a story worked well for teaching folks why things needed to be the way they were:

Looking back now, the product architecture has generally held up since launch for both projects. At the time, in addition to implementing these products, I had to wait for a while after they launched for the product choices to prove themselves out with our users and for the technical choices to prove themselves out with engineers internally as they ramped up.

I think that’s an important criteria for Staff-plus Engineers in product: not to just build something that ships, but for it to roll out smoothly and continue to succeed and grow over time with as few regrettable choices as possible. There will always be corners cut and features descoped during product development, especially for new products. A Staff product engineer makes those product and technical choices deliberately, taking on various different user personas to make the best choice possible and documenting rough edges thoroughly for future engineers.

Did you have to put together a promotion packet?

When I was promoted to Staff, I was fortunate to have a manager who was extremely engaged in supporting my promotion. To be honest, at the time I didn’t really understand how to write my self-reviews the right way. I wrote self-reflective development plans for what I wanted to learn over the next year instead of documenting the impact and scope of my work. My manager actually did most of the work by writing out my impact in his review.

There were a couple of other things that helped me. First, I worked with the same manager for much of that time. If you change managers then your manager loses context and that pushes the work of creating continuity onto you. Second, my manager was managing a relatively small team and was able to spend a lot of time keeping track of and understanding the details of what I was working on. If I’d been reporting to a manager supporting say, 10+ engineers, I likely would have had to put a lot more work into my own promotion packet.

What two or three factors were most important for you to reach the Staff level?

Thinking back, a potentially-surprising important factor for me was (and is) my imposter syndrome. It made me extraordinarily open to feedback; to learning and growing and to taking responsibility for anything remotely related to my work. It made me proactively seek out feedback on everything from the validity of my comments on PRs to how I ran a particular meeting. If something was broken (whether it was technical or organizational), I felt unsettled and was deeply, intrinsically motivated to go learn about it and to fix it. No part of Stripe’s product was “not my problem.” This developed into two superpowers that are perhaps even more important to have as a Staff-plus Engineer than technical superpowers are:

- Truly listening to and empathizing with others.

- A deep care for solving all types of problems.

Of course, imposter syndrome is a double-edged sword. It often makes me scared and self-conscious—early on I constantly felt like I would get fired for not being fast or effective enough. I grew more secure about my own strengths over time, but to be frank, this took a lot of time and positive reinforcement from my managers and from leaders at the company.

Is it harder to reach Staff-plus roles when working in product engineering rather than in infrastructure engineering?

I do think that is the case. I also think it’s a bit easier at Stripe, where the core product is infrastructure. This means there are many opportunities within product engineering to work on projects that need to consider scale, robustness, migration path, and well-designed interfaces.

It can definitely be tricky to reach Staff if you’re on a team that mostly builds UI, because UI products are by nature more temporary and allow for more iteration and experimentation. To reach the Staff level of impact as an engineer on a UI team, you need to be able to create leverage. You could do this by building well-designed component libraries, experimentation frameworks, etc.

Another aspect of building leverage as a product engineer is creating processes and systems to manage “product debt.” Folks often talk about “technical debt,” but equally important is the “product debt” caused by supporting old versions of your product, and much of the difficulty of product engineering at scale is related to managing product debt and product drift (that is, products that need to interoperate with each other moving in different directions) over time. I believe that a company’s accumulation of product debt does create Staff-complexity roles within product engineering at a certain scale.

Can you remember any piece of advice on reaching Staff that was particularly helpful for you?

I haven’t gotten much generically useful advice. There was good situation-specific advice that I got along the way, but those pieces of advice are always tied to the situations at hand.

The most useful general learning for me was becoming comfortable with uncertainty. Sustained success in senior roles depends on your ability to adapt and grow as the needs of the organization change.

Advice for someone who wants to become a Staff-plus engineer?

Some caveats:

- I think I’ve been particularly lucky with the managers I’ve had.

- My interests have always been aligned with what was most important for the company. (At this point it’s a bit unclear to me if my personal interests (i.e., developer products, mentorship) were aligned, or if over time I’d aligned myself to what was important for the company. I feel like it’s the former, but in either case, I feel like I’ve always been really interested in my work.)

I’m probably one of the most visible product engineers at the company, so engineers will sometimes see what I’m doing and try to pattern match on that to become a Staff-plus Engineer. That feels great, and I’m lucky to be able to be a role model for others like me.

That said, my first piece of advice to engineers is that they should avoid pattern matching in ways that lead them towards work they don’t enjoy. I’m deeply energized by the work I do, partnering with teams to solve abstract modeling and design problems. It takes a certain amount of fortitude to try again and again after many rounds of feedback, and to be honest, it’s not for everyone. If you’re more focused on hitting Staff than on setting yourself up to do work that energizes you, it’s easy to end up stuck in a role you don’t want. Being a Staff-plus Engineer, especially a broad-scoped Staff-plus Engineer, is a very different job than being a Senior Engineer.

Instead, pursue work that you find energizing, even if on paper it doesn’t seem like it’d get you to a Staff-plus. A big component of being successful as a Staff-plus Engineer is being able to identify and scope net-new impactful work and to convince others of its value and impact. If the work you’re doing energizes you, it’s actually much easier to achieve this because you’ll enjoy thinking deeply about your work a lot more!

What about advice for someone who has just started as a Staff-plus engineer?

Your job as a Staff-plus Engineer is specific to your team and organization, and it’s important to avoid taking advice that doesn’t apply to your situation. For example, when I moved into my current role, many of the other Staff-plus Engineers were focused on writing personal charters describing what they want to accomplish over the next 1-2 years. That approach likely works well for deep-scoped engineers, but it hasn’t been as helpful for me as a broad-scoped engineer who needs to respond quickly to organizational changes and shifts to product strategy.

Did you ever consider engineering management?

I do manage two engineers right now. That said, I don’t do a lot of the things that a traditional manager would do. I’m not involved in recruiting like a hiring manager would be, and I don’t experience the same sort of performance management situations that other managers would because the engineers who are selected for my team are already high performers.

I care a LOT about Stripe: when I see something out of place I feel antsy and want to fix it. In some organizations I think that could have led me towards engineering management rather than my current role, and I’m grateful that management wasn’t the only path that was available to me. My strengths and interests lie in product engineering and API design and execution, and I’m able to use these strengths every day in my role.

What are some resources (books, blogs, people, etc) you’ve learned from?

I love reading fiction and I learn a lot about the world from great literature. I don’t like reading non-fiction business or technical books nearly as much. When it comes to learning about topics more directly relevant to my job, I treasure my peer relationships. My peers give me valuable in-the-moment feedback and help me tease out the answers that were in my head all along.

Stripe also has a program called “Leadership In Practice” which is taken by all managers and some senior engineers. That program included a class on adaptive leadership which was particularly helpful. I’ve since applied the frameworks I learned to many situations.

I’ve never been a person who looks to a single mentor for advice. Instead, I follow what I used to call a “Frankenstein,” build-your-own-mentor approach, similar to what Lara Hogan wrote about in her post on building a manager voltron. Programs that match me up with a single mentor have never quite felt natural to me. I tend to be intentional about the particular topic or area I want to grow in, and will gravitate towards individuals who excel in that area, even if they’re not my “official” mentor.

I spend most of my time on hard, specific questions that don’t have an easy, generic answer. Figuring out the right approach requires a lot of situational context that someone outside the situation won’t have much insight into.

Some non-fiction that I’ve read recently and enjoyed:

- Draft No. 4, John McPhee: I spend most of my time writing at work, and experience writer’s block quite a bit. But it’s super important to power through that, because a good piece of written communication is the most effective means of broadcasting ideas and scaling yourself.

- Creativity Inc., Ed Catmull: The tone of this book definitely made me raise my eyebrows, but there’s a LOT to learn here about how to foster a creative working environment at scale. This is something I think about a lot as we grow our product organization and our product engineering function.

- Impro, Keith Johnstone: I see my superpower (especially as the company grows) as being able to learn and adapt quickly, so I love reading books about different forms of learning and teaching. This book is about learning how to act / improvise, and pushes on conventional metaphors and narratives about education.

Next chapter: Silvia Botros - Senior Principal Engineer at Twilio Inc.

Previous chapter: Rick Boone - Strategic Advisor to Uber's VP of Infrastructure

Book

If you've enjoyed reading the stories and guides on staffeng.com, you might also enjoy Staff Engineer: Leadership beyond the management track, which features many of these guides and stories.